By Christine Swan

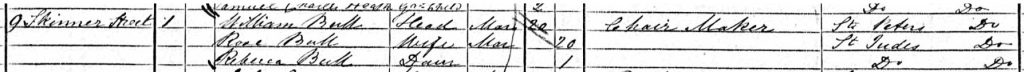

My great grandmother, Rebecca Bull, was born in Bristol in 1870. The family lived near the city centre, in the area where the Cabot Circus shopping centre now sits. Her father, William Henry Bull, was a chairmaker and her mother, Eliza Rosina, kept house. William Henry was drawn, as were so many, to do better for his family and, like so many, was drawn to London. In about 1878, the family left their native Bristol and William Henry moved himself, Eliza Rosina and their now five children to Shoreditch in the East of London. By 1881, two more children had joined the growing Bull family in Charles Street. Rebecca was twelve years old at this point and, as the oldest daughter, was probably involved in the care of her younger siblings.

The Bull family in Bristol in 1871

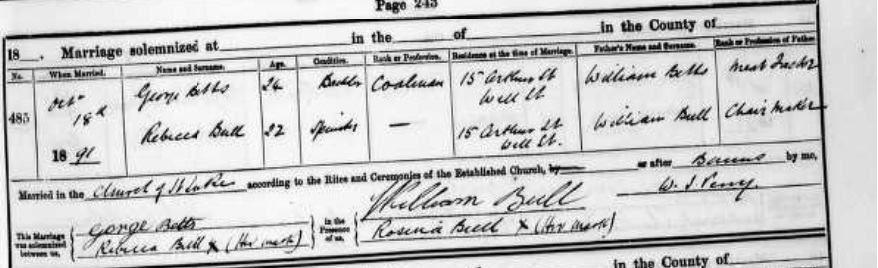

In 1891, at the time that the England census was taken, Rebecca

was recorded as visiting Richard and Elizabeth Johnstone in Holmbrook Street,

Homerton and working as a pickler. I am unsure what she was pickling, but in

the days before the refrigerator, this was an important way of preserving

produce to enjoy year round. George Betts was living in nearby in Milborne

Street, just twenty minutes walk away. The

census was taken in April but by October, Rebecca and George were married at St

Luke, Homerton Terrace when she was twenty two years old he, just two years

older. Rebecca’s parents were both witnesses to the marriage and while both

William Henry and George both signed their names, Eliza Rosina and Rebecca could

not. My father told me that Rebecca had never learned to read and write

although I have discovered a contradiction to this. It appears that it was

Rebecca who completed and signed the 1911 census.

Rebecca Bull working as a pickler in 1891

Unfortunately, Rebecca’s age meant that although the

Education Act of 1870 set up school boards to manage education provision in

their locality, attendance was not compulsory. A further act in 1880 made

Education compulsory for children aged between five and ten. Further acts in

1891 and 1899 increased the compulsory age to eleven and then twelve. Therefore,

many adults had to manage without being literate. Rebecca’s husband had

attended school by courtesy of the family of his biological father. By 1870,

when the first Education Act was implemented, it is estimated that 20% men were

illiterate and 25% of women (Lloyd, 2007). However, for working class families,

sending their children to school rather than to the factory, and subsequent

loss of earnings, meant that fewer were literate and there didn’t seem to be any

compulsion for parents to make their children attend. I would like to think

that at some point in her adult life, Rebecca did learn, perhaps instructed by

one of her older children, or even George. I cannot imagine the frustration of

living in a world where the written world is functional and necessary, but also

to be denied the ability to lose oneself in fiction or a beautiful poem.

Many adults were illiterate before the Education Act made school attendance compulsory

It seems that George and Rebecca were a well-matched pair and

my paternal grandmother and my own father, remember a happy home with much love

and kindness, but very little money. They had a large family but precarious

financial means of support. In the early days of their marriage, George and

Rebecca lived with her parents at 15 Ada Street, Hackney. This must have been

quite a squeeze as the Bulls still had five children living at home and, in

1892 Eliza Rosina Betts was the first child in the Betts brood. A second

daughter, Helena Rebecca, was born in 1895, but sadly, she died aged just one. Their

son George was born one year later and another daughter, Lizzie, in 1899.

Rebecca at a family wedding in the early 1920s

1911 saw the family living in Colchester Road and had been

joined by Ethel, Daisy, Louisa and Emily. The growing family struggled on

George’s irregular wages but, as his work ethic was legendary, so was Rebecca’s

ability to make something out of very little. My father remembered her huge

pots of stew, often shared with neighbours, who were similarly in need. As the

children grew, they were able to contribute to the family coffers which would

have helped. Rebecca would also attend funerals of those who had no family. She

felt that attending as a mourner would be of benefit and everyone who knew her

commented on her kindness. She would also collect clothing and distribute it to

those in need – a warm winter coat, or a pair of shoes with fewer holes. Her

mission in life was to make that of others more bearable. This goodness rubbed

off on her children, who were all kind and generous with what they had.

When my grandmother, Daisy, married, she lived next door to her parents. My father recounted that he would always visit his grandmother after school and that she would always have some delicious food for him. He would keep quiet when he returned home but sometimes, was just too full to eat his dinner, which caused Daisy to remind her mother not to spoil him, but, Rebecca couldn’t resist. “I was her favourite”, my dad would proudly claim, although I believe that Rebecca possessed the ability to make everyone believe that they were her favourite.

Rebecca died in 1937 and this dealt a devastating blow to

the family. My dad would become tearful when he remembered his adored granny.

She was the glue that held the family together, who met their needs in so many

ways. Everyone was a better person having known her. I asked my dad if he

remembered if Rebecca retained her Bristolian accent. He believed that she had,

although it was somewhat faded from years of living in London. Quite charmingly,

in the 1911 census, her birthplace is listed as “Bristle”, which I imagine her

saying, followed by “my lover”.

Leave a comment